Robert Sturman: Art and Allyship

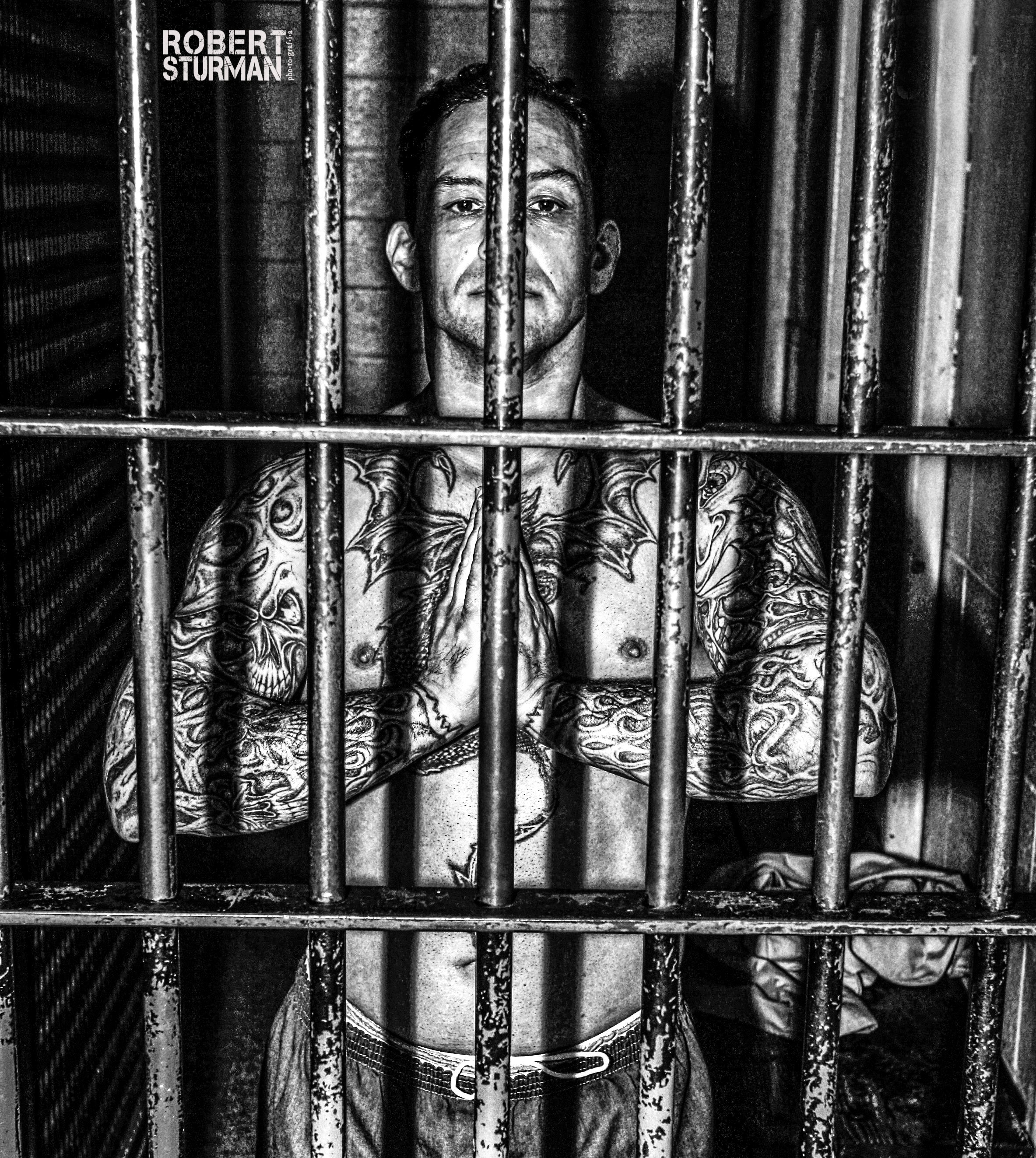

Robert Sturman is one of the first photographers to document yoga inside the California and Mexican prison system. His images have offered us insight into life behind bars, challenging assumptions about what tattooed inmates do and shown us the humanity and vulnerability of his subjects.

Pacho Viejo Penitentiary — Veracruz, Mexico

Making Better Choices

In 2011, at the invitation of a close friend who worked inside the prison system, Sturman visited Deuel Vocational Institute, a male prison in San Joaquin County, California, with a mandate to capture images of inmates practicing yoga. December of that year I accompanied Sturman to the prison to guest teach in the yoga program and facilitate a discussion with the inmates about their practice. It was an incredible experience.

Deuel is overcrowded and by all accounts violent. Yet the inmates I talked to demonstrated a very sophisticated grasp of the potency of yoga practice for inner transformation and its potential to affect change in myriad ways. To a man, they talked about how yoga helped them become less reactive, more equanimous, less invested in conflict on the prison floor. They talked about how much better their relationships were, with themselves, each other and their loved-ones outside. Later, in an extensive discussion about the efficacy of the yoga program the warden noted that the guys who participated made better choices.

I had never been inside a prison, nor spoken to an inmate yet I found their insights penetrating and relatable, their vulnerability touching. I too have struggled with equanimity and avoiding conflict. I too have made bad decisions that affected my relationships. I too am present to the rewards of yoga practice. It’s this very humanity, relatability and vulnerability that Sturman’s artistry captures. His images reflect the sincerity of his subjects’ practice. The hope, the surrender implicit in bowing towards the earth, the exultance (even behind bars) of opening the chest and heart in an expansive backbend. Sturman’s prison work causes us to reexamine our assumptions about those who are incarcerated and see their personhood, their beauty; it’s an invitation to empathy and the truth of our common humanity.

Deuel Vocational Institute — California State Prison

But Sturman’s empathetic eye also extends to the military and police officers. He has captured many images of uniformed personnel practicing yoga, images that nudge us to investigate our preconceived notions about what it means to be in particular roles. A soldier in a yoga pose beside a Blackhawk helicopter; a veteran doing a handstand on the beach, his two prosthetic legs beside him, his own cut off below the knee; a police officer backbending in the rain beside his vehicle.

The complexity of personhood and the different guises it assumes saturates Sturman’s work. If there’s an underlying theme, it’s our shared human experience and the wonder and beauty of embodiment.

Inner Excavation

Cut to 2003. With a couple of decades’ study of art and photography under his belt thirty-three-year-old Sturman does a stage in Europe, studying master painters and honing his craft. The trip is fruitful and impacts his self-understanding and his art. As if the two could be pulled apart.

A few years earlier he had spent several months in India and Nepal observing the culture and documenting sadhus, yogis and monks. The visibility of contemplative strands of society, the way the sacred and profane swirled around each other, living side by side, affected Sturman deeply and catalyzed his own inner expeditions. Yoga and spiritual practice would become an important part of his own life and influence his work enormously. His yoga photography has become known all over the world and includes an array of subjects from well-known yoga teachers, to Maasai tribespeople, yoginis in Santa Monica, inmates in San Quentin prison and more.

Time alone in Europe immersing himself in the work and lives of masters like Picasso, Michelangelo and Rodin further crystalized insights Sturman had in India about his art and his purpose, how the artist is responding to the world around him while simultaneously excavating some part of himself.

Sturman’s work is deeply personal, he repudiates the journalistic credo of objectivity citing Picasso speaking in 1937 when he composed his anti-war painting Guernica:

“artists who live and work with spiritual values cannot and should not remain indifferent to a conflict in which the highest values of humanity and civilization are at stake.”

Painted in response to the bombing of the Basque town, Guernica, by Nazi Germany and Facist Italy, it’s considered one of the most potent artistic critiques of war ever made. How interesting then that Sturman ended his European sojourn in Poland with a visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Harrowing for anyone no doubt, but particularly so for him, given his Jewish heritage. While there he saw a photo of a young Jewish boy, Abraham Beem, who at the tender age of nine years was deported from Holland and murdered on arrival. The image blew something apart in Sturman, in his own words:

“it inspired me to make use of this life that I have. The reality that so many children had their possibility thwarted triggered in me the resolve to make my life count. To take on the responsibility of making art with impact, to use the privilege of being alive to do my part in uplifting humanity and making sense of the world. I knew I could help make the world a better place.”

Back in Los Angeles Sturman kept the flame alive in his heart and went on to create an exquisite body of work documenting the Los Angeles yoga scene as well as working with the GRAMMY awards. A series of trips to Cuba (2000 – 2002) to document the vibrant culture and colorful music scene yielded a portfolio that got the attention of the GRAMMY committee and in 2005 he was selected as the official artist of the 47th GRAMMY awards. The artwork marking the awards was the first time ever that a musician was represented alongside the official logo. Sturman’s vision took him to East LA where several years prior he had met a Cuban street musician. Their collaboration made history and vivified Sturman’s connection with, and affinity for, musicians. His love of both yoga and music is reflected throughout his body of work and has influenced his life in unexpected ways.

Though Sturman’s finely honed aesthetic and technical mastery is always evident, his most arresting pieces go beyond the merely beautiful. He has not shied away from photographing breast cancer survivors, scars fully visible, nor amputees. His prison portfolio comprises incarcerated women and men in the USA, Mexico and Kenya. The images are powerful, moments of grace and depth juxtaposed with barred cells and standard issue uniforms that seek to strip inmates of their individuality and self-expression. Yet that expression comes through in Sturman’s shots, it’s in the eyes, the particularity of each person’s embodiment of a yoga pose. The practice itself is the great leveler, a vehicle for self-exploration, maybe even transformation.

A crucial part of Sturman’s own story is his particular pas de deux with history. His own creation myth was started when he discovered the lies at the heart of much of what he’d been told about American history. His self-conception as an artist, not merely a documentarian, was directly informed by his months in Continental Europe studying some of the great masters; a period that birthed his realization that not only was he standing on the shoulder of giants like Michelangelo and Picasso but that he too had a place in the lineage of artists whose work and lives uplifted the world.

His epiphany at Auschwitz that the gift of life brought with it an obligation to make a meaningful contribution to the story of humanity further solidified his understanding that the role of the artist cannot be separated from the society around him. That creativity can reach beyond entertainment to meet the moment in society and gesture at the ethical, the transformational.

Black Lives Matter

So it should not be surprising that the murder of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests inspired Sturman to a new level of artistry and engagement with the world around him. When protests erupted in Los Angeles last summer Sturman knew he had to be there, had to bear witness to the moment, to portray the fervor and emotion of the protestors. The series is breath-taking. He channels the righteous anger and emotional intensity of the protestors while simultaneously capturing the truth of their cause.

The images are unflinching and powerful, as always artfully composed. Sturman’s skill at getting the shot at just the right moment on full display yet subservient to the message being conveyed by the protestors, we are human, our lives matter; don’t kill us we deserve to live, we want to live. This is the year 2020 in the second largest city in the country that is the supposed leader of the free world. The mind boggles, the heart aches, the chest tightens. Men, women, children. Black skin, brown skin, Americans of color seeking justice, if that’s what it’s called when you simply want the right to live and equal treatment before the law.

One image seared itself into my consciousness. A dad and young son walking hand in hand both carrying signs, beside them a lone woman right arm held high in the black power salute. A church in the background. Dad walks tall and proud, masked wearing a Juneteenth t-shirt and carrying a Black Lives Matter sign staring straight ahead. The little boy is maybe eight or ten years old, masked and carrying a sign My Future Matters. This in itself is arresting and heart-wrenching but it’s the look on his face that gives the image such potency. His brow is creased, his eyes troubled, serious. A look that no child should wear. No child should have to worry about whether his future matters.

Black Live Matter Protest — Los Angeles, California

When I asked Sturman about his photos of the protests last summer he said he knew he had to document such a momentous occasion, wanted to do his part to not just memorialize the protests but also bear witness to the struggle for racial justice. The portfolio is stunning, the immediacy of the images stark. There is no wiggle room here. Sturman’s benevolent eye captures the irreducible message of the protestors, the weariness of the struggle but also the resolve for change, unwillingness to tolerate the status quo, peacefully demanding better.

It’s notable that Sturman became known worldwide as a yoga photographer. 2020 was the year when some of the cracks in the veneer of the yoga world became fissures; here in the USA it has been revealed to be a microcosm of the macrocosm with all the attendant problems of spiritual bypassing, privilege, white supremacy and toxic positivity. Some of us are committed to changing that, to doing and being better. Getting behind the movement for racial justice is part of the effort.

Black Lives Matter Protest — Downtown Los Angeles, California

As usual, Sturman was at the vanguard bringing his empathetic eye to his craft and engagement with society. Given his track record, it’s not surprising. But also given this: when Sturman was a fifteen year old high school student one of his teachers told the class that everything they’d been taught about America was bullshit. The exceptionalism, the greatest nation on earth, freedom, the founding myths. The elision of history concerning slavery and genocide. The realization opened his mind and ignited a commitment to justice and digging deeper into the truth of America. I can’t wait to see what he does next. I know it’ll be deep and important.